The "Good Enough" Paradox: A Science-Backed Life Trap

Today at a Glance

What’s a Rich Text element?

The rich text element allows you to create and format headings, paragraphs, blockquotes, images, and video all in one place instead of having to add and format them individually. Just double-click and easily create content.

Static and dynamic content editing

A rich text element can be used with static or dynamic content. For static content, just drop it into any page and begin editing. For dynamic content, add a rich text field to any collection and then connect a rich text element to that field in the settings panel. !

- ml;xsml;xa

- koxsaml;xsml;xsa

- mklxsaml;xsa

How to customize formatting for each rich text

Headings, paragraphs, blockquotes, figures, images, and figure captions can all be styled after a class is added to the rich text element using the "When inside of" nested selector system.

Last week, I read a research paper from a group of Harvard and UCLA psychologists that I can't stop thinking about.

Its title grabbed me immediately: The peculiar longevity of things not so bad.

The 2004 paper explores a paradox in how people recover from negative experiences.

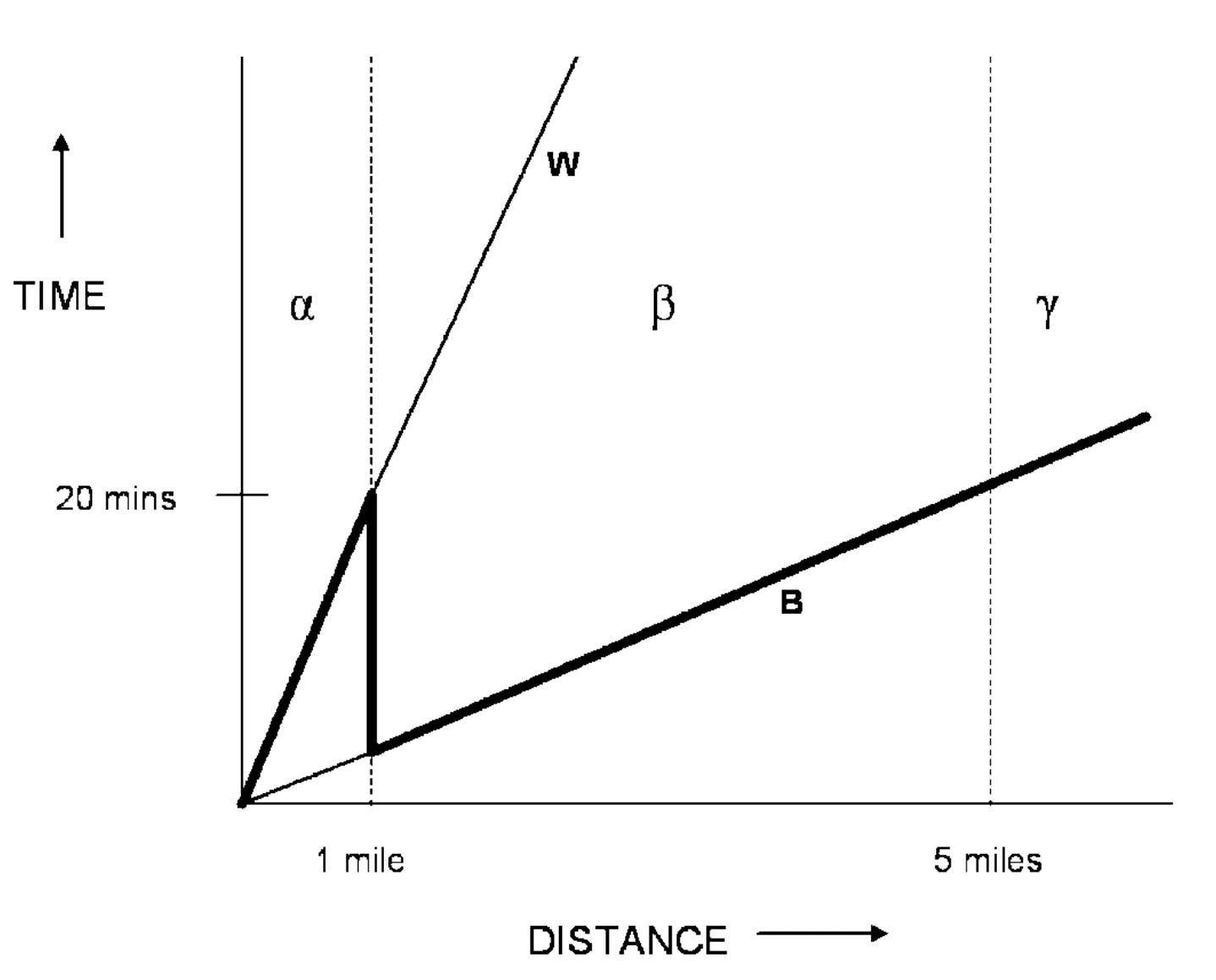

Consider a person choosing whether to walk or bike to a destination. The person will most likely choose to walk for short distances and bike for longer distances. This creates a paradoxical situation where a person will arrive at a more distant destination faster than a closer one.

This is the basis for the Region-Beta Paradox, highlighted by the image below:

The bold line shows a person who walks to destinations less than a mile away and bikes to destinations over a mile away. This person will reach any point in region Beta faster than any point in region Alpha.

As you might have guessed, this paradox applies well beyond modes of travel. It shows up in the most impactful realms of our lives.

The researchers ran a series of clever experiments to see whether our predictions of the intensity and duration of negative feelings match our experienced reality.

In one experiment, 98 participants imagined a list of negative events—from being turned down for a date to their best friend having a romantic encounter with their former partner.

For each event, they were asked to estimate:

- How intensely they'd feel the negative emotion.

- How long that emotion would last (by judging how they would feel about it one week later).

The researchers found a strong linear expectation between the initial intensity and the expected duration. In other words, people believed that more intense pain lasts longer.

But interestingly, the researchers note, this isn't true in practice, because people respond to their circumstances.

The researchers write:

When a spoon falls off a table...the duration of its descent depends entirely on its initial position...for objects that do not actively respond to their circumstances, the relation between time and distance is strictly monotonic.

In contrast, for objects that do actively respond to their circumstances, the relation between time and distance can become briefly nonmonotonic.

Humans respond to their circumstances—and this changes everything.

We act quickly to resolve intensely negative or painful experiences with a series of built-in adaptive processes.

So, our predictions for how long a negative state will last are wrong:

Intense negative experiences often resolve faster than mild ones. Because we act, consciously or subconsciously, to resolve them.

This has a variety of meaningful implications for your life.

When something is good enough, it lasts longer than when something is bad, simply because you won't take action to change it.

The 3/10 job. The 3/10 relationship. The 3/10 life. Those break you open. They force change with the intensity of the negative experience. You hit the threshold of pain that activates every psychological and behavioral mechanism you have.

But the 6/10? That's the trap of good enough.

It's not painful enough to trigger action. So you drift. You tolerate. You wait. You stay in jobs you've outgrown. In relationships that don't nourish. In routines that feel hollow. Because they're just good enough to avoid sparking a response.

The worst thing in the world isn't being on a bad path. The worst thing in the world is being on a good path that isn't yours.

The bad path screams for change. The good path that isn't yours sits in silence.

The Region-Beta Paradox reminds us of the dangers of good enough.

It takes courage to escape the trap. You have to force action. You have to choose uncertainty over comfort. You have to make the cost of inaction feel higher than the cost of action.

And here's an important truth to remember:

Courage isn't courageous because it works out. Courage is courageous because you act without knowing that it will.